Piecing together the epic battle of Gettysburg, I’ve found such dramatic stories of Providence, that…in the words of one commander, ‘Only a fool or infidel could deny’ the hand of God in it all. Shelby Foote, the famous Civil War historian, once commented that it was ‘as if the very stars aligned in their courses against Lee’ at Gettysburg, to draw him into battle and then to cause him to throw his men away in Pickett’s [or Longstreet’s] charge on the third day.

And, that seems to be the case. The little details, the ‘chance’ occurrences of terrain, men and events, were arranged in such a way that the Federals won the battle. The more one studies the battle, the more these details pile up and leap out…as an avalanche of ‘improbable’ events, men and positions, piled one upon another, to turn back the Confederate tide.

Among this tide of providential details is the story of Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain and the 20th Maine.

I’ve commented before on the character of this man, and the actions of the 20th at Gettysburg. But here, I’d like to set up the context of those days in July so that readers can sense the power of events for themselves.

The battle at Gettysburg engaged on the first of July, where, by all accounts…the Confederates smashed the Federal troops, with heavy losses. The 20th Maine and the Fifth Corps spent this day marching, only to find themselves 16 or so miles from Gettysburg and the crucial battle by night’s end.

A night when the powers of another world drew nigh

July 1, 1863

The Fifth Corps marched to Hanover, Pennsylvania – Col. Chamberlain and the 20th Maine lay down by the road to get some rest…only to receive urgent orders: ‘Get up and march to Gettysburg!’

Nightfall brought us to Hanover, Pennsylvania, and to a halt. And it was the evening of the first day of July, 1863. All day we had been marching north from Maryland, searching and pushing out on all roads for the hoped-for collision with [Gen. Robert E.] Lee eagerly, hurriedly, yet cautiously, with skirmishers and flankers out to sound the first challenge, and our main body ready for the call…

Worn and famished we stacked arms in camping order, hoping to bivouac beside them… Some of the forage wagons had now got up, and there was a brief rally at their tail ends for quick justice to be dispensed. But the unregenerate fires had hardly blackened the coffee-dippers, and the hardtack hardly been hammered into working order by the bayonet shanks, when everything was stopped short by whispers of disaster away on the left: the enemy had struck our columns at Gettysburg, and driven it back with terrible loss; [John F.] Reynolds, the commander, had been killed, and the remnant scarcely able to hold on to the hillsides unless rescue came before morning. These were only rumors flitting owl-like, in the gathering shadows. We could not quite believe them, but they deepened our mood.

Suddenly the startling bugle-call from unseen headquarters! “The General!” it rang! “To the march! No moment of delay!”

Word was coming, too. Staff officers dashed from corps, to division, to brigade, to regiment, to battery and the order flew like the hawk, and not the owl. “To Gettysburg!” it said -- a forced march of sixteen miles. But what forced it? And what opposed? Not supper, nor sleep, nor sore feet and aching limbs.

In a moment, the whole corps was in marching order; rest, rations, earth itself forgotten; one thought -- to be first on that Gettysburg road. The iron-faced veterans were transformed to boys. They insisted on starting out with colors flying, so that even the night might know what manner of men were coming to redeem the day.

At a turn of the road a staff officer, with an air of authority, told each colonel as he came riding up, that McClellan was in command again, and riding ahead of us on the road. Then wild cheers rolled from the crowding column into the brooding sky, and the earth shook under the quickened tread. Now from a dark angle of the roadside came a whisper, whether from earthly or unearthly voice one cannot feel quite sure, that the august form of Washington had been seen that afternoon at sunset riding over the Gettysburg hills. Let no one smile at me! I half believed it myself -- so did the powers of the other world draw nigh![1]

So after their 12 hour march to Hanover, PA, without rest or cooked rations, they force-marched all night to reach Gettysburg by the 2nd of July.

Hold this ground at all costs!

July 2, 1863

They reached Gettysburg in the morning, and slept on their arms beside the road.

Again the bugle ordered them forward. They entered the field to general chaos and disorder. Amidst the shells and cries for help, Col. Vincent, their commanding officer, heard that Little Round Top was unprotected. Without divisional orders, immediately ordered the Fifth Corps forward, and placed the little 20th Maine on the end of the line.

Reaching the southern face of Little Round Top, I found Vincent there, with intense poise and look. He said with a voice of awe, as if translating the tables of the eternal law, ‘I place you here! This is the left of the Union line. You understand. You are to hold this ground at all costs!’

Chamberlain said that ‘he understood, but was yet to learn about costs.’ He prepared his men to fight ‘at all costs,’ i.e. to fight to the death, if need be.[2]

Captain Howard Prince later related the actions of Chamberlain in the moments before the battle:

Up and down the line, with a last word of encouragement or caution, walks the quiet man, whose calm exterior concealed the fire of the warrior and heart of steel, whose careful dispositions and ready resource, whose unswerving courage and audacious nerve in the last desperate crisis, are to crown himself and his faithful soldiers with...fadeless laurels.[3]

In less than 10 minutes they were attacked. They had literally reached the decisive point of the battle with only minutes to spare.

Immediately, members of the 4th and 47th Alabama regiments attacked their front, and the 20th Maine was hotly engaged.

During the attack, an adjutant alerted Chamberlain a movement of Confederates between the Round Tops towards his left flank. He climbed a rock to see this new development, and sure enough…behind the main attack line, the 500 man 15th Alabama under Colonel William C. Oates was stealthily moving to enfilade his left flank.

But he had no more men for the flank!

Coolly, he ordered his men to keep firing, and take several steps to the left. In this manner he lengthened the thin line, then doubled them back at a right angle. In military terms, this is called ‘refusing the line.’ And he did it under extreme fire, totally outmanned. When the 15th Alabama charged in, instead of crushing an unprotected line, they met a volley of fire, which stunned them and threw them back. “The execution of this difficult maneuver while under fire is a tribute to the regiment’s training and discipline and to Chamberlain’s resourcefulness.”[4]

However, this move, as brilliant as it was, only postponed the inevitable. The 20th Maine just simply didn’t’ have enough men or firepower to hold the position. Their line was spread too thin, and now almost doubled back upon itself.

The roar of all this tumult reached us on the left, and heightened the intensity of our resolve. Meanwhile the flanking column worked around to our left and joined with those before us in a fierce assault, which lasted with increasing fury for an intense hour. The two lines met and broke and mingled in the shock. The crush of musketry gave way to cuts and thrusts, grapplings and wrestlings. The edge of conflict swayed to and from, with wild whirlpools and eddies. At times I saw around me more of the enemy than of my own men: gaps opening, swallowing, closing again with sharp convulsive energy; squads of stalwart men who had cut their way through us, disappearing as if translated. All around, strange, mingled roar-shouts of defiance, rally, and desperation; and underneath, murmured entreaty and stifled moans; gasping prayers, snatches of Sabbath song, whispers of loved names; everywhere men torn and broken, staggering, creeping quivering on the earth, and dead faces with strangely fixed eyes staring stark into the sky. Things which cannot be told -- nor dreamed.

How men held on, each one knows, not I. But manhood commands admiration.

There was one fine young fellow, who had been cut down early in the fight with a ghastly wound across his forehead, and who I had thought might possibly be saved with prompt attention. So I had sent him back to our little field hospital, at least to die in peace. Within a half-hour, in a desperate rally I saw that noble youth amidst the rolling smoke as an apparition from the dead, with bloody bandage for the only covering of his head, in the thick of the fight, high-borne and pressing on as they that shall see death no more. I shall know him when I see him again, on whatever shore![5]

After an hour and a half of this desperate fighting, the little 20th Maine had nothing left to give. Facing 3-1 or 4-1 odds, on little sleep, two-days march, and low ammunition, they could not stand another blow. Six times the enemy had assaulted them. Five times their thin line had been penetrated and almost shattered. The seventh assault would be their last.

Our thin line was broken, and the enemy were in rear of the whole Round Top defense -- infantry, artillery, humanity itself -- with the Round Top and the day theirs. Now, too, our fire was slackening; our last rounds of shot had been fired; what I had sent for could not get to us. I saw the faces of my men one after another, when they had fired their last cartridge, turn anxiously towards mine for a moment; then square to the front again. To the front for them lay death; to the rear what they would die to save…

In his battle report, Chamberlain described it this way:

The enemy seemed to have gathered all their energies for their final assault. We had gotten our thin line into as good a shape as possible, when a strong force emerged from the scrub wood in the valley, as well as I could judge, in two lines in echelon by the right, and, opening a heavy fire, the first line came on as if they meant to sweep everything before them. We opened on them as well as we could with our scanty ammunition snatched from the field.

It did not seem possible to withstand another shock like this now coming on. Our loss had been severe. One-half of my left wing had fallen, and a third of my regiment lay just behind us, dead or badly wounded. At this moment my anxiety was increased by a great roar of musketry in my rear, on the farther or northerly slope of Little Round Top, apparently on the flank of the regular brigade, which was in support of Hazlett's battery on the crest behind us. The bullets from this attack struck into my left rear, and I feared that the enemy might have nearly surrounded the Little Round Top, and only a desperate chance was left for us. My ammunition was soon exhausted. My men were firing their last shot and getting ready to “club” their muskets.

It was imperative to strike before we were struck by this overwhelming force in a hand-to-hand fight, which we could not probably have withstood or survived. At that crisis, I ordered the bayonet. The word was enough. It ran like fire along the line, from man to man, and rose into a shout, with which they sprang forward upon the enemy, now not 30 yards away. The effect was surprising; many of the enemy's first line threw down their arms and surrendered. An officer fired his pistol at my head with one hand, while he handed me his sword with the other. Holding fast by our right, and swinging forward our left, we made an extended “right wheel,” before which the enemy's second line broke and fell back, fighting from tree to tree, many being captured, until we had swept the valley and cleared the front of nearly our entire brigade.[6]

It was a glorious, improbable victory. Entering the fight with 358 men, only 200 remained for the charge… In the charge, these 200 took 400 prisoners, from 5 different Confederate regiments…which gives a sense of the magnitude of the assault force before them – battle hardened regiments from Hood’s and Longstreet’s divisions yielding to a thin blue Federal line bereft of ammunition!

Colonel Oates of the 15th Alabama would later write: “There never were harder fighters than the 20th Maine men and their gallant Colonel. His skill and persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat. Great events sometimes turn on comparatively small affairs.”[7]

Singular guidance of Providence

- A scholar and professor, Chamberlain should not have been in battle. His college did not permit him to join, so he took several days leave of absence and signed up!

- He was not West Point trained; yet he trained himself and the regiment into one of the best in the Union Army.

- God gifted him with a brilliant mind, trained in classics, half dozen languages, and professor of logic, rhetoric and theology. He turned this brilliance toward understanding the art of war, and understanding men…gifted with the intuitive ability to react instantly to crucial battle demands. Chamberlain commented in a letter to his wife Fanny: “I study, I tell you, every military work I can find. And it is no small labor to master the evolutions of a Battalion and Brigade. I am bound to understand everything.”

- Of all the Federal officers, none were more creatively equipped than Chamberlain -- intellectually, spiritually or martially -- to be in this exact position that July day in Gettysburg.

- Of all the Federal regiments, none were more able, man for man, than the 20th Maine [who reflected the leadership of their Col., and trusted him implicitly] to be on the end of the line at Little Round Top.

- Twice during the battle Chamberlain was wounded. And several times, seemingly protected by Providence: 1. An opposing officer fired a pistol in his face, point blank, only to have it misfire; 2. An opposing Alabama marksman twice had something ‘queer’ come down on him, when he had Chamberlain in his sights.

Dear Sir: I want to tell you of a little passage in the battle of Round Top, Gettysburg concerning you and me, which I am now glad of. Twice in that fight I had your life in my hands. I got a safe place between two rocks, and drew bead fair and square on you. You were standing in the open behind the center of your line, full exposed. I knew your rank by your uniform and your actions, and I thought it a mighty good thing to put you out of the way. I rested my gun on the rock and took steady aim. I started to pull the trigger, but some queer notion stopped me. Then I got ashamed of my weakness and went through the same motions again. I had you, perfectly certain. But that same queer something shut right down on me. I couldn’t pull the trigger, and gave it up - that is, your life. I am glad of it now, and hope you are.[8]

- The 20th Maine formed at Camp Mason in Portland, and under Colonel Ames. Colonel Ames was a notoriously brutal commander, who drilled the men so hard that Chamberlain’s younger brother, Tom, feared that the men would shoot Ames at the first chance, commenting thus: “...Colonel Ames takes the men out to drill and he will damn them up hill and down... I tell you he is about as savage a man you ever saw.” Only after their first combat did the men realize that this over-the-top discipline ensured their survival. Their training made them as close to an elite fighting force as the Civil War knew.

- The 20th Maine came to Gettysburg after enduring some of the most deadly fighting of the war, at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Originally mustering close to 900 men, they reported to the line at Gettysburg with 358 men and 28 officers, and this including the addition of 120 court-martialed men from the 2nd Maine, whom Chamberlain convinced to fight with them.

- The 20th Maine was the Marine Corps of the Federals: trained and proven in the harshest circumstances, almost as if for a single moment in time…holding the line on the rocky slopes of Little Round Top.

The spiritual nature of sacrifice for others

Chamberlain insisted, with great passion, that the sacrifice of his men at Gettysburg and on other fields, be characterized in spiritual terms, as part of the glorious cosmic war against darkness. For this honor, this high chivalry, he paid a price.

Some have said that his stubborn ethics, his code of valor cost him the Senate, and perhaps Presidency…as political enemies undermined him, since they couldn’t control him. But that’s just the kind of man he was. He would not sell out…no, not even for the Senate or President’s power.

The picture of the man is seen, years later, sitting on Little Round Top:

I sat there alone, on the storied crest, till the sun went down as it did before over the misty hills, and the darkness crept up the slopes, till from all earthly sight I was buried as with those before. But oh, what radiant companionship rose around, what steadfast ranks of power, what bearing of heroic souls. Oh, the glory that beamed through those nights and days. Nobody will ever know it here! I am sorry most of all for that the proud young valor that rose above the mortal, and then at last was mortal after all; the chivalry of hand and heart that in other days and other lands would have sent their names ringing down in song and story!

They did not know it themselves -- those boys of ours whose remembered faces in every home should be cherished symbols of the true, for life or death -- what were their lofty deeds of body, mind, heart, soul on that tremendous day.

Unknown -- but kept! The earth itself shall be its treasurer. It holds something of ours besides graves. These strange influences of material nature, its mountains and seas, its sunset skies and nights of stars, its colors and tones and odors, carry something of the mutual, reciprocal. It is a sympathy. On that other side it is represented to us as suffering: The whole creation travailing in pain together, in earnest expectation, waiting for the adoption -- having the right, then, to something which is to be its own.

And so these Gettysburg hills which lifted up such splendid valor, and drank in such high heart's blood, shall hold the mighty secret in their bosom till the great day of revelation and recompense, when these heights shall flame again with transfigured light -- they, too, have part in that adoption, which is the manifestation of the sons of God!

Rutherford B. Johnson comments:

Such characteristics of subordinating one's own selfish ends to the furtherance of a noble, important, and often life-and-death cause are sorely lacking in today's mainstream society. It is not that they do not exist, but rather that those feeling likewise are fewer today than in certain previous times, and often those feelings are greatly suppressed by popular culture. Yet, in this struggle for the preservation of freedom and indeed our very existence, such characteristics are most essential. Chief among these is moral courage and an inclination to carry out actions, when called, which, no matter how unpleasant or self-endangering, are essential to achieving victory.[9]

It is an abiding lesson of courage, and living to ‘the limits of the soul’s ideal.’

Such Providence, in making the man, and bringing the man to bear in these circumstances, should cause us to reflect on our own greatness, and place in the cosmic war between good and evil.

We were not at Gettysburg. But the good done in private, by a good man or woman, carries on the sacrifice…it ensures that the deeds of valor done on this field, and others, for freedom…were not done in vain. It also echoes again that that highest of deeds from the greatest Warrior of all time…on the Cross…still speaks for victory!

Brave hearts, good hearts, continue still…

Dust of heroes, we will know you...on whatever shore!

“In great deeds something abides. On great fields something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls. And reverent men and women from afar, and generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream; and lo! The shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.”

_________________________

1 Joshua L. Chamberlain, Through Blood and Fire at Gettysburg, published in Gettysburg Magazine No. 6, January 1992 and also published online.

This casual hint of Chamberlain, ‘so did the powers of the other world draw nigh,’ intimates the first real ghost story of Gettysburg: The form of Gen. Washington, dead for 63 years, was reported on the road to Gettysburg, at a crossroads; and then, on the battlefield, at the crucial moment of the bayonet charge: So many of the 15th Alabama claimed to have seen the form of Washington leading the charge that the War Department investigated following the war. And, again, Chamberlain cryptically comments, “Those brave Alabama fellows-- none braver or better in either army--were victims…of their quick and mobile imagination.”

2 Michael Nugent comments:

Chamberlain fully understood the criticality of his mission. If the Confederate forces were able to flank his position, they would gain the rear of the entire Union line with disastrous results… What Chamberlain could not have known, was that in the event of a significant Confederate victory during General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania, the leaders of the Confederacy intended to present President Lincoln with an offer to pursue a negotiated peace, potentially dividing the Country permanently. [Nugent, “Joshua L. Chamberlain: a Biographical Essay,” Military History Online .3 Recounted by Pat Finegan, To the Limits of the Soul’s Ideal: My Tribute to Major General Joshua L. Chamberlain.

4 Nugent, “Chamberlain.”

5 Joshua L. Chamberlain, Through Blood and Fire at Gettysburg, published in Gettysburg Magazine No. 6, January 1992 and online.

6 Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain's Report of the Battle of Gettysburg (20th Maine), The American Civil War.

7 Quoted by Nugent, “Chamberlain.”

8 Chamberlain, Through Blood and Fire at Gettysburg.

9 Rutherford B. Johnson, A Personal Essay about Chamberlain's Philosophy, and its Modern Application.

Key resources for further study:

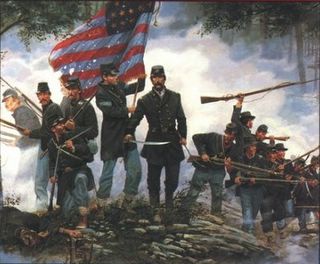

Joshua L. Chamberlain, Bayonet! Forward: My Civil War Reminences, Stan Clark Military Books, 1994. The opening picture of Chamberlain on the horse, colors behind him, is from the cover of this book.

Joshua L. Chamberlain, Through Blood and Fire at Gettysburg, Stan Clark Military Books, 1994. The closing, fighting action picture of Chamberlain holding the sword, with the 20th Maine on Little Round Top, is from the cover of this book.

Alice Rains Trulock. In the Hands of Providence: Joshua L. Chamberlain and the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

To the limits of the soul's ideal. This is a very informative website published by Pat Finegan, on Chamberlain. Lots of nuggets here, in these pages.

No comments:

Post a Comment